One of the learnings from the extraordinary public health, social and economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the depth and duration of which is yet to be fully experienced, is to clearly identify and deliberately find solutions to each ‘next highest priority’ problem, based on best available evidence.

Such a considered process is now needed with regards to recovery of Australia’s post-schooling tertiary ‘education, training and skilling[1]’ (ETS) system, given the rapid, massive, and still uncertain scale of disruption caused by the pandemic. This is most immediately evident in Australia’s temporarily stalled education and training of international students.

The near term need is to provide re-skilling and up-skilling opportunities for job seekers and displaced workers, mindful of the evidence of wide differences in job loss and disadvantage by occupation types, age and gender. In the longer term a reinvigorated ETS-system must support accelerated productivity and economic growth, including smarter self-reliance in strategic goods and supply chains.

This article has a two-fold purpose. The first is to review key ‘pre-pandemic’ reform proposals with regards to the nation’s ETS-system, with focus mostly on the VET sector, viewed through the new lens point of rapid COVID-19-driven government policy and funding interventions. This flows into the second interconnected purpose which is to make general (indeed speculative) comment on how the pandemic may reshape Australia’s present ETS-system – positively if the opportunity is taken.

Summary status of the ETS-system reform agenda pre-pandemic

The status of key reforms includes: the Australian Government had accepted all recommendations of the Review of the Australian Qualifications Framework (AQF), but its final form is yet to be detailed and agreed by all jurisdictions (it spans HE and VET sectors) and implemented; the Australian Government had likewise accepted the recommendations of the Review of the Higher Education Provider Category Standards, but these too are not yet implemented; the Australian Government is implementing the recommendations of the Expert Review of Australia’s VET system to the extent of its budgeted commitments including establishing the National Skills Commission (NSC) and National Careers Institute; all jurisdictions had agreed at COAG a vision for the VET sector and the national Treasurer had tasked the Productivity Commission (PC) to review the National Agreement for Skills and Workforce Development (NASWD). Its interim report is pending. The COAG Skills Council is to present a final VET reform ‘road map’ to First Ministers by mid-2020.

The pandemic struck and reform energies have been temporarily re-directed. Governments and institutions quickly responded to protect the interests of students and employees to best preserve the functions and fabric of the ETS system – a system exposed as being deeply reliant on ongoing public funding and financing of its activities. Table 1 lists examples. Most criticism has been lack of government support for enrolled international students and in re-building this student market (but see recent NSW Government support).

Table 1: Examples of government responses to support Australia tertiary ETS system

| Cwlth | Higher Education Relief Package. Online short courses at universities. Apprentice/trainees. Online course information. Fast track training package changes. |

| NSW | Free TAFE courses tosupport NSW student to upskill during pandemic. TAFE NSW fee free online courses |

| Vic | Skilling up Victorians to get through the coronavirus crisis; |

| Qld | Coronavirus (COVID-19): Free online training courses for individuals and business; Job Finder Recruitment support. |

| SA | VET market continuity package to support non-government training providers |

| WA | Support package for construction workforce - Short-term lending facility e.g. for universities |

| Tas | Rapid Response Skills Initiative training and job support |

| ACT | Skilled Capital Qualification and Skill Set List. Amended |

Repair to the past or rebuild for the future

Any recovery can be planned to either get back to roughly the same place on the same terms, or, be used as opportunity for a reform minded re-build under revised policy. As one example: a modest injection of as many as 20,000 ‘short course or micro-credentials’ delivered by universities is: either a temporary fix; or a pilot of a future permanent adjustment that early anticipates recommendations of the recent AQF Review. There are then either ‘temporary fix’ solutions, or decisions to re-build with foresight and integrated purpose. There are multiple challenges across the ETS-system in what is now predicted as a long climb up, but probably not back, to the same shape. One example is wider adjustment to student expectations in ‘on-line’ delivery. Another is the impending severe loss and best slow recovery of university research outputs.

‘Roadmaps’ are not traversed quickly without decisive ‘cooperatively funded propulsion’

The lesson from the response to the national pandemic is that you identify and fix things in order of coordinated priority based on national benefit, with federal cooperation. You don’t get bewildered or busily dispersed by the multiplicity of moving parts or lower sub-order interests. For example, why campaign to re-brand VET/TAFE when its basic funding/financing model, compared with universities, is so disadvantaged.

Whilst the draft COAG VET Reform Roadmap is commendably clear in its organisational principles and its presentation, simply redecorating the same issues long known to be VET’s troubled topography won’t now cut it, especially as the generalised ‘what success looks like (i.e. end state)’ outcomes across seven separate ‘destinations’ are as much as 4-5 years away. This won’t clear ‘road congestion’ especially given the pace of the COVID-inspired decision making, and the need to support fast regrowth in jobs and the economy with a greater skilled labour force. Such a slack timeframe now looks downright limp.

Encouragingly the COAG Skills Council has just agreed to a revised approach to the draft VET Reform Roadmap in light of the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic to now structure it around the pandemic crisis response, economic recovery, and long-term reforms. So to the future…

‘First and foremost sort out the details of the main game’ – tertiary system funding and financing

COAG made clear in its Vision: “VET and higher education are equal and integral parts of a joined up and accessible post-secondary education system with pathways between VET, higher education and the school system” and “delivering high quality VET is a shared responsibility across the Commonwealth and States and Territories”. If this direction is not clear, read the PM’s riding instructions to the new Department.

First, the creation of a Department of Education, Skills and Employment that consolidates the current Department of Education and Department of Employment Skills, Small and Family Business. This is about having continuity from the day you walk into school to the day you walk into a job and beyond, and ensuring that in your job and over your life, we understand that there is a continuous education. Education doesn't start and stop when you leave school. It goes on over your entire life. Learning happens in the workplace. Skills development happens in the school. It happens at university, at TAFE and vocational training. It's a lifelong activity. Well into senior years. And I want a public service agency department that is focused on that continuity of policy and service delivery and engagement with the states[2]”.

Standing then above all other issues is the quantum of governments support (training subsidies and loans) nationally available for VET and the long term sustainable contributions by all governments. As previously detailed VET will be little helped by ‘simpler’ funding alone with the recent Expert Review (Rec. 2.4 pp 32) only exhorting governments to ‘commit over time to reducing the differential in the level of student funding support at a particular AQF level between qualification-based vocational education and university education’.

This meekly points at the root cause and offers no solution. Importantly also, the details of the game have now moved on, given the Australian Government has also accepted recommendations for a revised AQF.

The core issue all governments need to address is the lack of a coherent, federally supported and nationally operating tertiary funding framework that spans the AQF. Australia needs to conceptualise and build a nationally operating post-school ETS funding and financing (i.e. loans) framework that is federally agreed by all governments and that spans all AQF levels (as may be amended) that supports both school leavers and existing workers, fully covering their ‘work-life’ learning needs.

All students must have fair and equitable access to course funding. Funding of universities should remain as recently settled, including growth funding. Any new design must future proof a higher skilled workforce providing funding/financing for both ‘new entrant’ workers to further raise workforce participation as well as support existing workers for ‘up and re-skilling’. It should publicly fund/finance both VET/HE level full qualifications and ‘short-form’ courses/credentials, taking consideration of course quality and relevance, student equity, as well as relative public vs private (student/employer) investment and benefit.

Integrated AQF and tertiary-system funding/financing reform is the needed ‘propulsion engine’

At risk of oversimplification, the Commonwealth alone own, manage, fund and finance Australia’s HE sector by dint of constitutional right and weight of public resourcing. By contrast, the States own, manage and fund Australia’s VET sector on a basis of ‘cooperative federalism’ by multiparty agreement with the Commonwealth, with the latter both funding/financing training as well as related training costs, e.g. apprentice subsidies.

The party’s roles and responsibilities (both joint and separate) are outlined in the now 10 year old NASWD, with annual grants provided under the Intergovernmental Agreement on Federal Financial Relations to part support State and Territory costs of training. This is the crux of the PC Review.

Whilst some argue one level of government should own, operate and resource the whole ETS system (an option rejected by First Minister’s at COAG), the ETS system has and will retain a cross over junction from one (HE) to multiple (VET) resource provider(s) and stakeholders. Any new deal must accommodate this.

Late in 2019, the Australian Government, by announcement of both relevant Commonwealth Ministers, accepted in full the recommendations[3] of the Review of the AQF. The current AQF is defining of HE/VET sectors and in setting levels, differences and specific overlaps between all HE and VET qualifications.

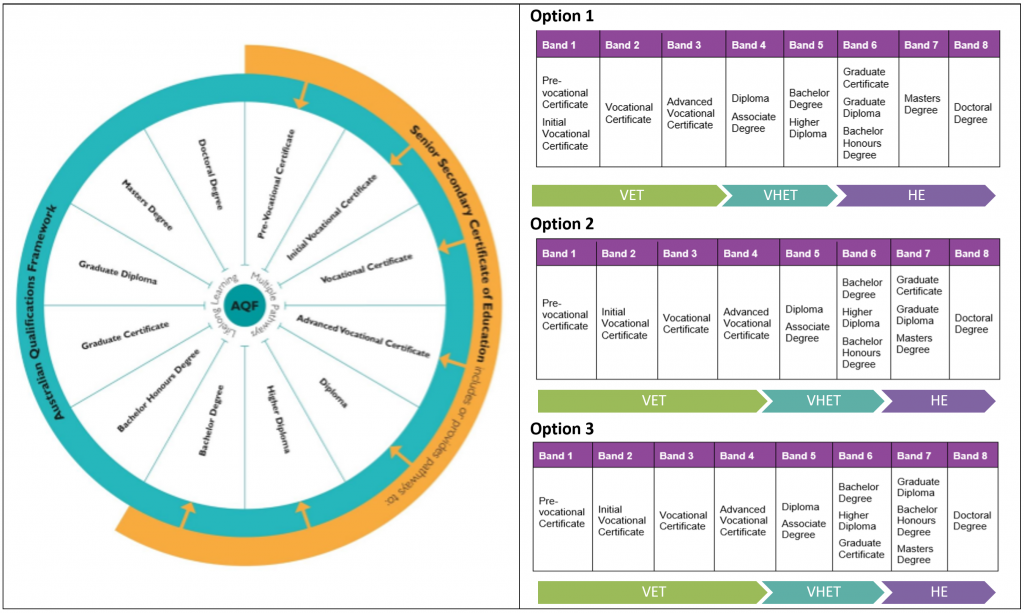

The Review proposed the present 10 ‘level’ AQF be replaced by a new AQF with eight ‘bands’ representing complexity of knowledge, six bands representing skills and a third category of application, which recognises that there are different ways learners can demonstrate acquired knowledge and skills. It’s a richer way of describing qualifications accommodating greater flexibility in design (e.g. micro-credentials and skills sets) and in promoting enhanced sectoral pathways opportunities. It is an imaginatively crafted modernisation of the AQF.

“Under a revised AQF, it would therefore be less meaningful to represent qualification types as directly aligned to bands. This reduces the need to show the AQF as a hierarchy of qualifications aligned to rigid and locked levels, and allows it to be shown as a spectrum of qualifications” Review of the AQF pp. 41.

The Review did not decide but offered three options for best translation of 10 AQF ‘levels’ into 8 AQF ‘bands’ (Figure 1). In doing so it specifically considered the contextual research and concerns about current AQF levels 5 and 6 and concluded the present VET/HE distinction at AQF 5/6 levels be eliminated so “combining current AQF Levels 5 and 6 could lead to the current Diploma, Associate Degree and Advanced Diploma being co-located (as the) Panel believes it would be undesirable to have two different diplomas at the same level (and also) proposes creating a (new) Higher Diploma in both VET and higher education at the same band as the Bachelor Degree” Review of the AQF pp. 43. Lastly a new governance body, accountable to the relevant Council of Australian Governments (COAG) is to sort through all implementation details.

Figure 1: The revised AQF qualifications and 3 options for flexibly positioning qualifications in ‘bands’

So, if governments have in the past based their funding/financing on the qualification levels in the current AQF, what then if the revised flexible qualification banding of either Options 1, or 2 or 3, or some other, is adopted? Where then are the cooperative funding boundaries/continuums? On what basis are State Premiers going to understand future long term State funding commitments to VET if the definitional basis of VET and HE qualifications, long anchored to the 10 level AQF, is up for reforms and re setting of details.

And also, if there is to be no longer distinction between HE and VET at AQF 5/6 (i.e. they are all in Band 4 in Option 1, or Band 5, in both Option 2 and 3 as per Figure 1); what is the future ongoing purpose of the Commonwealth running two discrete and inequitable funding programs; VET Student Loans and all its policy and program costs, and the HE institutional allocation of designated places for sub-bachelor courses? At least consider making friends with new ideas as the AQF is being reformed.

Pandemic inspired short course funding intervention and future AQF HE vs VET implications

The motive of governments to quickly put in place suitable education and up-skilling of workers displaced by the pandemic crisis is not in question. Table 1 lists initiatives. It is how this is done and the permanency of such crisis policy that will, in time, be up for question, specifically the Commonwealth’s intervention in funding online ‘short-courses’ at higher education levels.

The initiative is for some 20,000 places in national priority areas such as nursing, teaching, health, IT and science. The costs have been discounted for students and the universities have been required to offer and commence courses by May 2020 to initially run for six months. The offerings by universities have been prompt and extensive as listed on course seeker[4]. It has given new opportunities for students as well as potential revenue to universities/HE providers (although discounted and perhaps temporary).

The issues of interest are that the ‘undergraduate certificate’ did not exist in the AQF and as explained by Professor Andrew Norton it was hastily legitimated by an AQF addendum, presumably by jurisdictional agreement. As Norton points out, not only is the AQF and its qualification levels embedded in legislative, policy, administrative, professional accreditation and industrial governance, it is also sectoral defining and so relevant to public funding and financing of the entire tertiary system, both VET and HE.

The second observation is that a high proportion of the short courses (both undergraduate and graduate certificate) are in areas of current highest enrolments and outputs in VET at higher level Certificate III/IV and Diplomas e.g. aged care, child care, nursing as well as many high demand areas offered in VET e.g. IT/cyber etc.

Norton also points out risks of student and employer confusion in certification. Lastly, from a quality and regulatory perspective the content of such university ‘certificates’ are overseen by speedy self-accrediting governance, unlike rigid VET processes where the AISC has been charged with driving rapid and flexible development of training packages during the crisis, with reported progress being made in critical skills.

Whilst these pandemic-driven arrangements may be temporary, with the new AQF addendum to be reviewed at the end of 2021, it is an example of where the historic divide of HE and VET sectors, whilst true and enduring at extreme ends, is increasingly blurred and being treated less so.

The national Education Minister’s rhetoric on university graduates needing to be ‘job ready’ is akin to VET’s long held purpose and is now formally partly tied to future university growth funding. The HE short courses, although laudable in themselves, further test boundaries of governments’ roles and mutual funding/financing.

A new National Agreement – compromises and accountability required

Assuming then there to be a renewed NA, it will need considerable compromise by all parties in the best interests of ‘cooperative federalism’. Jurisdictions know well enough the Expert Review did not directly consider adequacy of VET’s funding, nor offer solutions on how to increase investment in VET (public, private or employer), nor any solutions to fund (where appropriate) part qualifications/micro credentials/subjects, nor covers the merits and reasons for wider access to student loans (as occurs in other federalised systems like Canada) and did not examine differences and continuity of VET/HE funding and financing systems.

Jurisdictions seek new partnering approaches. They want collaborative processes, including shared knowledge and data on skills shortages and course costing benchmarks. But on the basis of their constitutional right and principles of subsidiarity, they resist centralised steerage of skills demand forecasting and most especially do not accept centralised setting of skills priorities and course pricing. Read Table 2.

Table 2: Extracts from jurisdictional submissions to the Productivity Commission Review of NASWD

| NSW | ‘The position of the NSW Government (is) that the next iteration of the NASWD be underpinned by the concepts of national aspiration with bilateral implementation; …..advocates a revised approach …that re-imagines the way the Commonwealth and NSW governments work together by, introducing joint cross-jurisdictional decision-making; ..an agreed set of targets with agreed contribution from the Commonwealth towards achieving NSW’s share of the these targets; …a bilateral agreement that recognises that both ….contribute funding to the VET sector ….working together on a skills and workforce development agenda that spans schooling, VET sector and higher education. NSW will continue to review its own system …maintaining a relevant and targeted Skills List. New South Wales Government Submission December 2019 |

| Vic. | ‘The Victorian Government has a successful track record of managing its government funded VET system….; national funding arrangements should recognise and respect the role of State and Territory governments in managing their VET systems, and provide flexibility for jurisdictions to determine resource allocations ….Victoria has a robust system to assess the qualifications demand in Victoria and is best placed to make decisions regarding how training activity can best align with the needs of the Victorian economy; …the Commonwealth and States and Territories work together to strengthen the links and connection across the entire post-secondary education and training sector, with simpler and more transparent pathways and credit arrangements; and, national funding arrangements should … be sufficient enough to enable quality training delivery that supports students to gain genuine employment outcomes that are responsive to industry and community needs. Victorian Government Submission January 2020 |

| Qld | ‘As co-owners of the national training system, [I] … express my strong desire to have arrangements in place that provide funding certainty for Queensland, share financial risk and allow Queensland to appropriately manage its skills and training budget. …. It is critical that the role of the state, as the majority funder of VET, is not encroached upon, particularly in relation to pricing and subsidy setting… States and territories fundamentally require flexibility in their funding efforts and should not be exposed to onerous conditions and input controls that are contrary to the principles of the Intergovernmental Agreement on Federal Financial Relations. [I am] pleased the Review will consider …consistency in funding and loan arrangements between the VET and higher education. Ministerial letter as Queensland Government Submission January 2020 |

| SA | ‘South Australia is strongly of the view that to be effective the VET system needs to combine national consistency in relation to such things as regulation with responsive local (state and territory) funding and management of training services. There is an opportunity to coordinate or consolidate national capability to support knowledge development, including in relation to costing and performance benchmarking, as a resource and reference for all jurisdictions and stakeholders. The governance mechanisms… in the Joyce Review, could provide an institutional foundation for national governance but only if designed within the framework of cooperative federalism. South Australian Government Submission December 2019 |

| WA | ‘The State…requires a ….VET sector that retains the flexibility and autonomy to respond to local demand, industry needs and government priorities; WA has challenges …[a] unique geographic, demographic and industry characteristics,…these ….present as unique skill needs, thin markets and higher costs to deliver VET; the State has robust frameworks for skills demand forecasting, setting priorities and pricing and does not support recommendations of the Joyce Review to centralise these functions or set nationally consistent priorities or prices; priority should be given to the inequity in Commonwealth funding arrangements between the VET and higher education sectors, including differences in the availability of income-contingent student loans Western Australia Government Submission December 2019 |

| Tas. | ‘The strength of VET in Australia is in its federated structure, where national consistency and standards are supported by system flexibility to address local priorities and needs. (and)….believes that any proposed changes to the VET system should: focus on delivering consistent outcomes rather than consistent processes; ..that a ‘one size fits all’ approach may not provide the best outcomes; not inhibit the ability of the VET system to respond rapidly to local training priorities; maintain the integrated approach to learning across the Education and Skills sectors that the Tasmanian Government has worked hard to develop’. Tasmanian Government Submission December 2019 |

| ACT | ‘The ACT's unique labour market …means that its VET sector is quite different from …other jurisdictions. In addition to traditional VET qualifications, such as those in the skilled trades, key support roles across knowledge sectors depend on VET-qualified workers with mid-level technical skills (equivalent to AQF levels 5-6). The overall higher skill level of the workforce, in combination with a growing knowledge sector, means that higher VET qualifications are more in demand in the ACT than in other states and territories….That a national approach to funding and pricing would not necessarily account for the statistically small but key differences of the ACT's. Australian Capital Territory Submission December 2019 |

Source: Compiled from public submissions to the Productivity Commission on NASWD

Clearly the Commonwealth want reasonable accountability (for its present ~$1.6 billion NA funded annually) in any new arrangement, or the States risk the Commonwealth, as a fall back, offering a new NASWD with no funds transfer. Key past issues have been: States maintaining a fair share of funding; divergent subsidises and pricing of same courses; and, diversity in types of courses subsidised. A new NA can dealt with this.

One: Maintain proportionate mutual investment. States and Territories should be funded under specific bilateral (sub NA) agreements proportionate to what they invest. Run on an annualised basis, if States don’t keep up with the Commonwealth’s indexed funding, others States where they exceed their agreed share could get more from the NA. This will discourage (and expose) those State Treasuries disinvesting in VET.

Two: informed, flexible and nationally monitored pricing. There is no ‘market’ rationale for subsidies and pricing being the same across the nation as costs are not the same. There are possible efficient mechanisms to create information on public investment per course per provider linkable to provider-specific student outcomes. This would give granular data to funders to drive quality and efficiency improvements (better quality may be justified by higher costs). All governments must commit to share information.

Three: Collaborate on industry intelligence and data analytics: Joyce is reported as saying: “Australia is about to face high dislocation and high unemployment which will put skills education and university under a lot of pressure. Skills education has its origins in state-based TAFEs which are motivated by state government needs, which increasingly do not reflect the infrastructure and technology needs of the nation” – a view seemingly at odds with those of States and Territories (Table 2) – and that, “The Prime Minister …..would like to have an organisation that will provide unimpeachable advice on what the skills are that are missing”. If this is the ‘one source of truth’ argument, the states are saying there are different measures of such truths depending on which patch of Australia for which each State Minister has responsibility. Minister’s will work with but not rely on a fleet of Canberra based data scientists, and will retain their own data capability. Nor will they discard or disregard their local industry intelligence. This all risks rank overbuild and duplication unless the NSC’s mission, governance and powers is truly collaborative in all it does, from top to bottom.

It is noted the consultation feedback on the NSC’s scope and workings does not yet detail its representative governance and powers. History shows such bodies get ‘plugged in and out’ of VET governance architecture.

Major forces and factors that might now go to re-shape the nation’s ETS system

Any past generalisations that universities are advantaged over the VET sector by virtue of: relatively settled policies and secure funding/financing, maturity of sector regulation, and greater product prestige in attracting students; whilst still standing, is part dented. The pandemic has squashed forecast revenues at many universities, other than those guaranteed in the HE Relief Package (Table 1). The mid-term solvency of universities will depend on their ability to fast remove costs or delay planned expenditure, to recover from their risk positions and, in some cases, over leveraged dependency on international student revenue. Learned opinion is that institutions have widely differing exposures based on past growth/risk decisions of their governing bodies. Fall outs and consequences are now emerging in job losses and renegotiated industrial arrangements. The depth and duration of contraction remains uncertain – so what speculatively may be the biggest changes in the future?

One probability is higher student-led expectations of online learning across the tertiary system. Ideally institutional ‘technology enhanced learning capabilities’ will all lift, facilitated by clear regulatory guidance.

A major concern however is a sharp contraction in the nation’s collective research outputs. The risks and gravity of this has been summarised by the Australian Academy of Sciences with regards to the losses across the nation’s research workforce, with a prolonged fall in Australia’s university research outputs and cooperative investment with industry, and an overall diminished national R&D with productivity loss. Research not only defines the status of ‘university’, it is research excellence and outputs that are potent factors in setting rankings and prestige. Universities will preferentially protect all research revenues as well as their best research talent, including faculty, domestic and international research students. Competition for available (e.g. public) funds for research will then intensify, further widening the performance spread of research income as reported in HERDC. Expert view is also that university costs of teaching are growing at a faster rate than indexation in government funding which ‘debunks the long-held assertion that the quantum of government funding for teaching and scholarship includes a component for research’.

The Review of Higher Education Provider Category Standards, affirmed ‘research is, and should remain, a defining feature of what it means to be a university in Australia’ and recommended the ‘threshold benchmark of quality and quantity of research … be included in the Higher Education Provider Category Standards and the threshold benchmark for research quality should also be augmented over time’.

Whilst improbable in the extreme any current university would forgo its privileged title, research funding pressures make it increasingly possible that a regulator may conclude a university does not reach the needed thresholds in research quality and output[5]. The Review did not directly address institutions exiting from university status, rather it more considered institutions aspiring to this status. It also recommended that requirements related to ‘industry engagement...... should be introduced or bolstered in the university categories of the Higher Education Provider Category Standards’ including the proposed ‘National Institute of Higher Education’ (NIHE) category, renamed by Government as ‘University Colleges’.

As observation and not correlation, universities quick to offer HE short courses (above), especially those in the Undergraduate Certificate category are dominantly those in the lowest third ranking by way of research income. As aftermath of COVID-19 , it is likely universities ‘world-class’ research capabilities and outputs will stretch even further apart, and so widen again existing differences in their missions and market positioning.

Whilst the Review canvased and rejected ‘polytechnic’ as a category title; noting it being a term ‘neither currently well understood nor consistently conceptualised in Australia’ pp.24, describing it as: ‘institute(s) of tertiary education, with most qualifications focussing on education around applied technology’; perhaps a future ETS-system needs to better recognise such institute types, deeply connected with industry.

Professor Braithwaite in her report “All eyes on quality: Review of the National Vocational Education and Training Regulator Act 2011” noted (pp 39):

A blurring education and training environment

In the past a sharp line has been drawn between education and training, teachers and trainers, and students and learners. The divide is captured by universities at one extreme with a quest to discover new knowledge, and vocational education at the other extreme with a quest to apply knowledge and develop practical skills. The distance between institutions that deliver academic and applied skills, however, is being fast whittled away. In part this is due to the technological revolution that requires everyone to sharpen and broaden problem-solving capacities. The traditional university agenda of discovery in a new age requires practical and operational skills. The traditional VET agenda of skill acquisition must deal with problem solving for skill transferability and skill adaptation. National productivity is seen today as dependent on synergy between the sectors. The other part of the story of the shrinking gap between higher education and VET is the explosion of jobs at the knowledge-skill interface. Childcare educators today aspire to a deeper knowledge of child development as well as having the skills to care for infants and young children. Three-dimensional printing of metal parts for traditional and as yet unknown uses is another example of where theory and application, university-based knowledge, and VET based knowledge, collide”.

Lastly, if the pandemic is to create a shake out across the ETS-system, it may yet be most evident in the VET sector. There are some 178 active HE providers regulated by TEQSA. This is way fewer than some 3,830 active Registered Training Organisations in the VET sector. RTOs (including TAFEs) are of vastly differing size. Many are small, even micro businesses, and are vulnerable as recognised by the Ministerial Council. Whilst a harsh outcome, an arguably positive change maybe (supported) mergers and/or takeovers amongst RTOs. This may, in the end, improve present market depth of viable providers in size, quality and cost efficiency. This would also give the major regulator ASQA, in implementing its recent fast review and refreshed regulatory philosophy and culture, the opportunity to work with a far smaller number of larger clients.

Productivity Commission now has an extraordinary opportunity

The PC in its report “Shifting the Dial Five Year Productivity Review” (Aug. 2017) in its Chapter titled ‘Future Skills and Work’ stated the ‘VET system is in a mess’ (pp. 86). The PC now has extraordinary opportunity to not only advise on the future of VET sector public funding, but to advance radical reforms to establish a comprehensive post schooling tertiary funding/financing system, suited to both school leavers and existing workers, to fully cover their ‘work-life’ learning, in both full or part qualifications (however named).

The PC needs to be bold and farsighted in presenting powerful options for radical reform of VET sector public funding as part of a comprehensive post schooling tertiary funding/financing system, and not as a limited response to the Expert Review whose analysis of VET funding is incomplete. Rather the PC should use this opportunity to confirm the Review of the AQF cannot be meaningfully implemented unless synchronised with national reform in funding/financing of Australia’s whole post schooling tertiary education system. Outcomes must be fair and equitable for students within a coherent, national ‘tertiary’ funding and loans framework that is federally supported by all governments and spans all AQF levels (however amended).

Deal with this first, with the same momentum and federated cooperation shown in getting national public health under control. Then steadily rebuild for the future by tackling next priority order ‘road map’ issues. The PC in guiding such first steps must ‘spear to the ground’ the conclusion that the renewal of the NASWD and NA, if isolated from comprehensive consideration of its place and connection within the whole tertiary ETS system, will not address Australia’s future human capital skills development for a competitive economy.

Dr Craig Fowler is an analyst and observer of national policies impacting tertiary education, science and innovation after decades of experience in private, public and university sectors.

[1] The nomenclature is deliberate: there are sectors being vocational education and training (VET)sector, higher education (HE) sector and also the employers/industries sector, each being essential collaborating participants within a national post schooling tertiary ETS system.

[2] Transcript of Prime Minister’s Press Conference Parliament House ACT 5 Dec 2019

[3] The wording was precise “The…Government today accepted all recommendations of the review in relation to higher education and accepted the aims of recommendations of the review in relation to vocational education contingent on further discussions with state and territory governments”.

[4] As at 18 May 2020 some 202 short courses are offered by 24 universities with 104 at as a Graduate Certificate and 98 titled under the new Undergraduate Certificate, only one Go8 university to date offers an undergraduate certificate.

[5] See Appendix D Recommended Categorisation and Criteria for Higher Education Providers

Email [email protected]

Campus Review The latest in higher education news

Campus Review The latest in higher education news

Dear Dr Fowler,

HOW MANY actual ‘trades mean and women’ were included in regard to the input/data/findings/recommendations related to the training pathway they need, want and desire – Apprentice > Advanced Trades > Specialised Trades > Master Crafts? Refer to article http://www.suppliermagazine.com.au, “It’s Not A Choice”, Oct/Nov 2016.

That is, not organisations or those who are ‘professionals’ ie university graduates who speak ‘for them’ and ‘about them’.

Yours faithfully,

Carolynne Bourne AM